“It rarely comes out the way you want it to,” said Ms. Ausby, 16, as she peered at the photograph, still wet from the chemicals used to make the print. “But when it does, it’s satisfying.”

As younger generations embrace vintage things — like vinyl records and early gaming consoles — more students have become interested in old-school photography, increasing the demand for analog photography classes in high schools across Manhattan.

And the High School of Fashion Industries is one of a handful of public schools that still offer analog photography classes. Schools with rigorous art programs and darkrooms have become the stewards of the dying practice that dominated the world for over a hundred years.

“Digital is too easy, in that you can take a lot of pictures at a time,” said Ben Russell, the photography teacher at the school. “Film slows you down because the amount of film limits you. It really makes you think about the photograph you’re creating.”

Using film, teachers said, helps students learn the fundamental elements of photography, and patience. The step-by-step, hands-on tinkering with chemicals and light exposure required to produce just a single photograph can take students several days.

“That slow process is valuable,” Mr. Russell said. “The other thing it teaches you is problem-solving skills because everything is computerized today. People don’t do things with their hands anymore.”

The school has offered analog photography classes for almost two decades in collaboration with the International Center of Photography, one of the world’s leading institutions dedicated to photography, based in Manhattan.

But it was once.

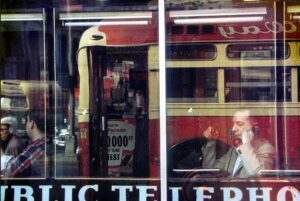

Inspired by street and documentary-based photography of the early 1900s, photography boomed in Manhattan between 1925 and 1950, when news organizations, advertising agencies and fashion firms began establishing themselves there.

City apartments were too small for darkrooms and equipment was expensive, so amateurs and professionals banded in clubs to create darkrooms for collective use across the city, Ellen Joan Handy, an associate professor of art history at the City College of New York, said.

Rental darkrooms became a common sight in the late 1960s in areas like the Flatiron district, sometimes known as the Photo District, a popular neighborhood for photographers seeking inexpensive lofts.

Colleges and art schools began offering photography classes and darkrooms started popping up in high schools across the country around the 1960s, Professor Handy said.

Their dark confines became the quiet sanctuary of students in photography courses, after-school photo clubs and student newspapers.

“There’s a sort of magic or drama from seeing an image appear from the chemicals,” Professor Handy said. “It connects students to the thrilling, wondrous aspects of photography a little more than the image just popping up on your phone.”

With the advent of digital cameras in the 1990s, digital photography soon eclipsed analog photography. In keeping with the times, most schools abandoned darkrooms or transformed them into digital computer labs.

Prices for film and analog equipment soared, and darkrooms became more expensive to maintain.

“I remember paying $1.99 for film that is now maybe like $5.99,” said Keith Miller, the photography teacher at Beacon High School in Hell’s Kitchen, who has been teaching analog photography there since 1998.

The school has a darkroom and around 50 cameras, but, he said, the program would not be possible without the financial support from the parents association.

“I feel it’s still a very worthwhile thing to teach,” said Mr. Miller, adding students also learn math and chemistry through analog photography.

As the film photography industry bounces back, many say the comeback has been fueled by young photographers who grew up in the digital era but long to experiment with the roots of the craft.

At the International Center of Photography, which offers analog photograph workshops to about 450 students a year, the waiting list continues to grow.

“It shows young people’s need for meditative spaces where they can practice patience,” Lacy Austin, the director of community programs at the center, said. “They’re so used to everything being so instantaneous that the idea of waiting for a photograph to emerge is something they’re really drawn to.”

Ms. Austin, a former public school teacher, estimated there are probably fewer than 10 public schools in the city with operational darkrooms.

“Teaching darkroom photography is a decision that is made by individual school communities based on their available space, curriculum and demand from students,” Paul King, the executive director of the Office of Arts & Special Projects at the city Department of Education, said in an email.

Teachers at schools with darkrooms said that analog photography is one of the most popular courses.

“Film photography is seen as this vintage, cool thing to do, like buying records,” said Lisa DiFilippo, the photography teacher at Millenium High School in the Financial District.

During a recent class there, two dozen students were developing film for the first time, a moment that many veteran photographers say they will never forget. Students had shot rolls of film the previous week and were anxious to see the results.

They followed Ms. DiFilippo’s instructions: protect the roll of film from light when placing it inside the container known as a funnel; mix the developer solution with water at a 1:1 ratio; pour the mixture into the funnel and agitate it so the film soaks in the chemicals.

Then, the students popped open their funnels. They unrolled their film and stretched it above their heads against the fluorescent lights, squinting at the strips of negatives.

There were oohs and ahhs. Some film had turned a cloudy purple, to the dismay of a handful of students. But most got to glimpse their work for the first time.

“Look, that’s so cool,” said Lucie Lagodich, a senior, without taking her eyes off her film. “We just mixed things.”