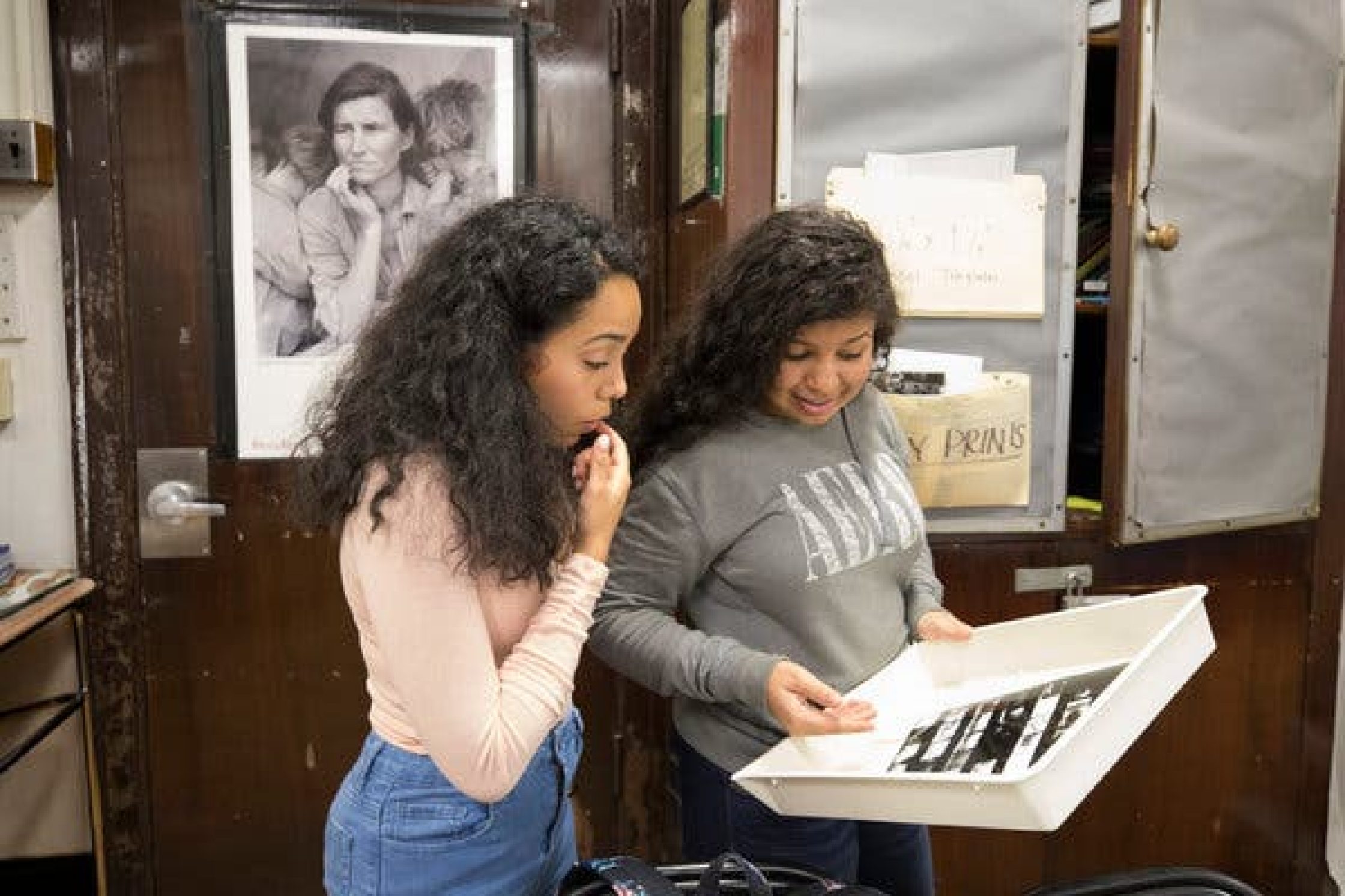

But as the new interim director of the photojournalism program at San Jose State University, he sees a school frozen in time. The darkroom was built in 1990, and its faucets had become corroded from photo-processing chemicals. The school replaced the faucets, but what it would really like is a digital lab.

The biggest problem is cameras: digital models that produce professional-quality work are expensive. ”Students can’t afford a $4,000 camera,” Mr. Gensheimer said. ”Some of them are buying the Canon D30 for a couple thousand dollars. Plus they have to buy memory cards for a few hundred dollars.”

Most schools don’t provide cameras for students and have concentrated on providing computer labs with Photoshop and other imaging software. Even San Jose State, in the heart of Silicon Valley, can barely get enough money from the state to afford software upgrades, Mr. Gensheimer said.

James Kenney, program coordinator for the photojournalism program at Western Kentucky University, described a similar predicament. He said the technology changes too fast for his university to keep up economically. Internships at newspapers have instead been the primary way that students learn how to operate digital cameras.

”The tools will always change,” he said. ”They’re in a constant state of flux. But we’re supposed to teach content, teach them to come up with good story ideas. We get so caught up in the tools, but the bottom line is we need to communicate good content, tell a good story. If we’re not doing that, no amount of bells and whistles will make any difference.”

As for darkrooms and the chemicals used to develop photos by hand, many instructors say they will become obsolete. But until students can afford professional-quality digital cameras, most schools will continue to use darkrooms and teach a decades-old process.